On October 26, 2024, the Alliance for Felix Cove hosted a reconciliation conversation between a Tamal-Ko (Tomales Bay Coast Miwok) family and a Point Reyes settler family. The settler family's ancestor, C.W. Howard--who owned most of the land on the west side of Tomales Bay--in 1887 hired Captain Henrik Claussen to evict all the Indians living on the west side of Tomales Bay. Their houses were destroyed and the people were forced to leave. One house remains standing at Felix Cove (Laird's Landing, used by the Lairds to ship dairy products to San Francisco 1860-1866). The last of the Felix family was evicted from their ancestral home by ranchers in 1952, and then later the ranches became part of the Point Reyes National Seashore--owned by all of us and managed for us by the National Park Service.

|

| Felix Cove in 2020 |

|

| Looking up Tomales Bay from above Felix Cove |

|

| The road to nearby Marshall Beach |

The thought-provoking conversation included how family members learned of their ancestors' history and how they feel about it, complete with long-overdue apologies. It also included discussion of reparations--specifically, returning Felix Cove to the now landless (aside from a recently-acquired parcel in Nicasio) and federally-unrecognized tribe. You can support their efforts here.

|

| Etcha Tamal, rematriated Coast Miwok Tribal Council land in Nicasio (photo taken in 2015 after pile burns, and prior to the 2023 purchase) |

The conversation was relevant to all of us, since we all are either indigenous to the land where we live or from somewhere else, and many of us from somewhere else have ancestors who came here and displaced the indigenous people. It felt personal to me, because I too have ancestors that pioneered a dairy industry in the 1850s on stolen indigenous land. And it made me realize that I too would like to apologize for those actions. This is that apology.

"At some point, you have to decide, are you going to live in a world of abundance, open-heartedness, and open-mindedness, or are you going to live in a world of exclusion, isolationism, and scarcity?"

--Theresa Harlan, founder of the Alliance for Felix Cove, describing why she laughed at herself when contacted by a descendant of the Point Reyes colonizers

The Story of My San Francisco Ancestors and the People They Displaced

When the Gold Rush brought the world to San Francisco in 1849, there was an Ohlone temescal (sweat house) that was on the beach where the new city started. This native structure was next to a small freshwater lagoon fed by streams (now the spot is at the corner of Montgomery and California). By January 1850 the population of San Francisco was 35,000, and in 1860 it was 56,802. Just imagine thousands of people suddenly overwhelming your home where you depended on fishing in the bay, hunting game in the hills, and collecting plants from the land. Some of those new arrivals were my ancestors.

My great-great-grandfather Henry Schwerin, 25 years old, arrived in San Francisco in January 1850 (after arriving in New York from Germany in 1848 on the ship Hanby Bk Adolf), joining his older brother Carl, who had arrived sometime before the previous June. After losing their Clay St. merchandizing business to a May 3-4, 1851 fire, by 1852 they started a restaurant at the corner of Washington St. and Dunbar Alley.

Just as the Onceler brought his family in The Lorax, Henry's soon-to-be wife (they married 8/3/1854) and mother arrived, and his brothers also came to San Francisco and started other businesses. And soon enough, there were no more truffala trees, humming fish, swomee swans, or bar-ba-loots.

|

| Color version of the 1847 view above, from the Library of Congress. |

|

| The view today. The Ohlone sweathouse, and the people who built it, are scattered and landless--their bayside home replaced by skyscrapers. |

Henry was looking for good grazing land for cattle raising. He turned back his option on a large parcel of sandy land where San Francisco City Hall is now located, and instead purchased 300 acres of bottom land in Visitacion Valley, where the Cow Palace is located today. He was taken with the springtime beauty of this valley--the blooming wildflowers, the oak trees, and two streams flowing through it--as well as the business prospects for farming and future real estate development. He tracked down the owner, William Pierce (who purchased the property 10 days earlier from Robert Eaton), and probably paid about $10,000 for it. Here the Spanish had previously raised cattle for Mission Dolores and the Presidio. Mexico had first granted this stolen Ohlone land, which they called Rancho Cañada de Guadalupe y Visitacion y Rancho Viejo, to Jacob Primer Leese in 1841 (after denying Manuel Sanchez's 1835 petition for the land).

|

| Diseño of Visitacion Valley. Spanish explorers discovered San Francisco Bay in 1769. In 1775, when they landed at Seashell Point (now Hunter's Point) they noted there were a few Ohlone from villages from the south, in what is now Visitacion Valley and Brisbane. The Spanish established the mission and presidio farther north in 1776, devastating the native population. Map courtesy of the late Russell R. Brabec and the Visitacion Valley History Project. |

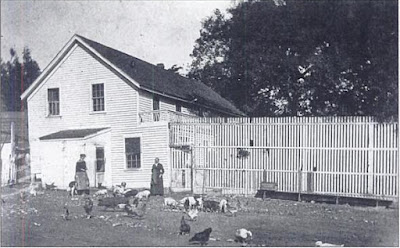

Henry had a house built (made of lumber shipped from France) near a spring in Visitacion Valley, and moved there by 1856. Henry and his wife Ottelia ran the ranch while their business partner William Schad ran the restaurant, for about two decades, until Schad died in 1877. The Schwerins planted eucalyptus trees as wind breaks, built a bunkhouse for workers, and profitably supplied butter, cheese, and eggs during a time when large quantities were being imported to San Francisco from the east. They also operated a nursery that sold cut flowers to the San Francisco Flower Market. In 1865 they split the ranch--the Schwerins kept 200 acres and Schad got 100 acres. Schad's property and wharf later became the Pacific Coal and Fertilizer Company. Other settlers followed, and "large truck gardens and nurseries flourished until World War II." (Visitacion Valley History Project, Images of America)

In 1868--the same year as one of the most destructive earthquakes in California history, the 6.8 "Great San Francisco Earthquake" on the Hayward Fault (a fault that has a large earthquake every 140 years and hasn't had one since)--Henry and others formed the Visitacion Valley Homestead subdivision project, naming the north-south streets Schiller, Goethe, Wieland, Gundlach, Spreckels, Hahn, Sawyer, Loehr, Britton, Rey, and Schwerin. The east-west streets were named Walbridge (since renamed Geneva), Ottilia, Reynolds, Martin, and Steinegger. In 1898, Henry sold most of the ranch and it was sectioned into house-size lots. The Schwerin Addition Project of 1908 (development accelerated after the 1906 earthquake and fire, when refugees from the city came to the Valley) and the Cow Palace project obliterated many of these names.

By 1881 Henry started a new restaurant on Clay St. between Montgomery and Kearny, and only spent weekends in Visitacion Valley. As of 1887 he had 120 cows and two wagons, and by 1896 he owned 100 cows and six horses. The Schwerin Dairy also had an outlet at 30th and Dolores, and an office and depot at 35 Eddy St. He owned a considerable amount of land in the Excelsior Homestead. By 1894 Schwerin & Sons operated the United States Restaurant on Clay between Montgomery and Sansome, a location once part of San Francisco Bay, later filled, and since 1972 occupied by the Transamerica Pyramid. The nearby Indian sweathouse, and the people who built it, were scattered and landless--their bayside home replaced by skyscrapers.

|

| Restaurant workers boycotted Henry's United States Restaurant. From the Daily Alta California, Vol. 40, No. 13442, June 16, 1886 |

Prior to Anglo colonization, the Yelamu tribe of the Ohlone had two villages in Visitacion Valley: Amuctac and Tubsinte. The San Francisco Bay tidelands supplied the Ohlone with vast quantities of clams and oysters, attested to by numerous mounds of discarded shells. There were three large mounds--

"One in the Sechini Truck Gardens, one back of the Six Mile House, and there is still one at the Bayshore in the old Marine Bone Yard. In these mounds were found many Indian skeletons. Mortars and flint arrowheads were found in abundance throughout the valley. The old Shell Road was so named owing to the fact that it was paved with the shells from the various shell mounds. Cattle were herded over the Shell Road to the slaughter houses of Miller and Lux at Butcher Town."

--4/28/1929 letter from Vena Schwerin (daughter of Edward, youngest son of Henry and Ottilia) to Mrs. Plumb (principal of the school built after Henry's became too small)

According to Brian Shea's Schwerin Family History, beavers, river otters, and sea otters also would have been abundant in one of the richest wildlife habitats in all of North America. Grizzly bears, foxes, mountain lions, bobcats, and coyotes were common. Quail, rabbits, deer, geese, fish, insects, lizards, snakes, moles, mice, gophers, ground squirrels, wood rats, doves, and bird eggs also would have provided plenty of food for the Ohone. But they did not eat ravens, owls, or frogs for religious reasons.

The Ohlone people used the marsh reeds for many purposes, including the construction of houses and boats and duck decoys. They made fish traps and snares.

"Neither the women nor the men wore footwear. Their feet were hardened by a lifetime of walking barefoot. Their figures were muscular, with rounded healthy features. Tattoos, mostly lines and dots, decorated their chins. The women wore necklaces made of abalone shells, clam-shell beads, olivella shells and feathers. These objects also served to decorate their infants basketry cradles. Some of the children played with tops and buzzers made out of acorns." --Brian Shea, Schwerin Family History

The tule huts were 6-8 feet in diameter, sometimes larger, made of reeds attached to a framework of bent willow branches. Inside, there was a central fire pit, surrounded by blankets of deer, bear, and rabbit skin. They used awls, bone scrapers, file stones, obsidian knives, and twist drills (for making holes in beads). They kept clay balls, ready to be ground into paint.

In spring the Ohlone migrated into the hills. They traded abalone shells for pine nuts with other tribes. They also "collected roots, clover, poppy, tansy-mustard, melic grass, miner's lettuce, mule ear shoots, cow parsnip shoots, and the new leaves of other plants. Some were eaten as salad greens; others were prepared as cooking greens. ...A year-round bounty of food was available. And their cooking techniques, handed down through the generations, made the food quite delicious." (Shea). Seeds, roots, dried meat, and dried fish were stored in hamper baskets. Soaproot was used for food, glue, and fish poison. In fall, the coast live oaks, valley oaks, and black oaks provided abundance for the acorn harvest. In winter they harvested mushrooms. Many plants had medicinal and other practical uses, such as milkweed fiber, hemp, basket materials, tobacco.

"Rather than valuing possessions these were a people who held natural generosity in high regard. Instead of doling out the inheritance after a person's death they would ritually destroy the goods. To be a leader among such people it was more a responsibility than a prestigious honor to be lavished. In fact the job was often turned down because it required so much from the individual. Warring between various tribes did occur, but it seemed to be rare. By the very style of their lives covetousness kept itself in a minimum position.

These were people whose lives were deeply ingrained in the seasons and in cycles. In migrations. In foraging and hunting. In food preparation. In preparation of the various implements of shelter and tools to aid them in sustaining themselves within nature's bounty. Their's were family oriented lives of social companionability." --Shea, with facts derived from "The Ohlone Way" written by Malcolm Margolin in 1978.

|

| Visitacion Valley had its own Oncelers (like in The Lorax). Quote from Brian Shea in his Schwerin Family History |

The devastation of this natural abundance cannot be reversed--Visitacion Valley is now city, due to my great-great-grandfather's (and others') subdivisions. I am sorry that my ancestors occupied and developed and sold this Ohlone land, permanently displacing the already-displaced native people, and I'm sorry that I and my family benefitted from that injustice.

What is next? What can we do now to make things better, or even reverse this outcome?

For the Ohlone, we can ask them what they need, and support efforts to rematriate indigenous land. For the land--the undeveloped hillsides and the marshes and the Bay--we can protect and restore ecological functions as much as possible. Wherever possible we can restore the living productive marshes and daylight the buried beautiful streams.

I work for Friends of the River to advocate for restoring more natural flows in California's rivers, which brings more natural salinity to San Francisco Bay and benefits the entire estuarine ecosystem, from fish, to birds, to marine mammals, to people. A little removed from the Bay and the subject of this blog post, but I also work for the Mono Lake Committee, where we are saving Mono Lake (again) from excessive water diversions to Los Angeles--and that helps birds on the entire Pacific Flyway, including the Bay Area).

We can stop using fossil fuels as much as possible, and vote for those who will help make that a rapid and just transition, which will keep global warming to a minimum. We can conserve water and energy, minimize consumption and waste, plant native plants, and conserve habitat for native wildlife. We can treat all people--including the descendants of the first inhabitants--with respect, and seek to learn from them how best to live sustainably on their ancestral lands.

And in Gary Snyder's words, "Stay together, learn the flowers, go light."

No comments:

Post a Comment